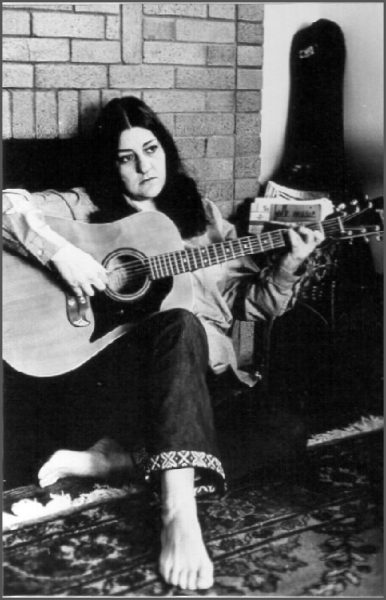

Madeline Davis

— singer, songwriter, activist, documentarian

— is one of the region’s most iconic gay

rights figures of the last 50 years. Her humble demeanor

belies the extensive work she’s forged on behalf

of the gay liberation movement during this seminal time,

but her words ring clear and true:

“The Stonewall Nation is gonna be

free.”

Madeline Davis

— singer, songwriter, activist, documentarian

— is one of the region’s most iconic gay

rights figures of the last 50 years. Her humble demeanor

belies the extensive work she’s forged on behalf

of the gay liberation movement during this seminal time,

but her words ring clear and true:

“The Stonewall Nation is gonna be

free.”

Born in 1940 and raised on the near East Side of Buffalo, New York, Madeline Davis didn’t come out as gay until the early 1960s. “I was already 21, 22, when I started coming out,” Madeline said.

“I say started because it was a process for me. I started sleeping with women, and then slept with men, as well, and then realized I liked sleeping with women better. I liked being with women better, I liked hanging out with women better.”

Being a young college student who sang and performed in coffeehouses at night, Madeline discovered a thriving gay and lesbian community in her city. And while there were people to commingle with in the bars, “being gay” wasn’t prevalent in daily life.

“Many people were not out at home, or even, certainly not at work,” she said. “There was always the fear that someone would ‘drop a dime’ on you. ‘Dropping a dime’ meant — that’s what a phone call cost at the time. That meant either calling your family or calling your workplace and exposing you as gay.

“So there was always that fear. There was also the fear of being invaded in your gay and lesbian space by mostly straight men, who would want to come in and disrupt whatever was going on, try to convince the women that they really wanted to be with men and that they should go home with them, and they were usually drunk, and they were young, and they were annoying, but we managed to persist,” Madeline said.

The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950 as one of the earliest LGBT organizations in the United States, took root throughout the country as a loosely connected network of people working to better conditions of gay and lesbian community members within their respective regions. In 1970, the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier came to be. A working librarian at the time, Madeline’s partner suggested she contribute her skillset to the cause, and build out a little library for the new community center.

“I tried to organize a library, which is very difficult when there’s hardly anything printed, you know?,” Madeline said. “There were some magazines around, and a few pamphlets and things like that… We moved a couch, and an easy chair, and a couple of other chairs into a room, and it became a place where people would hang out and not really read anything, because there wasn’t much to read,” she laughed. “Within a few months of the inception of Mattachine, I became a member.”

Anywhere between 60 and 200 people were active in the group at any given time during its heyday, Madeline said.

“We eventually went from one set of offices to another; our largest community center was what used to be a pool hall on the corner of Utica and Main St.,” she said. “It was wonderful. It was huge; somebody donated a bar from a bar that was being torn down, and it was gorgeous. It was one of those really nice ones, with a foot rail and lovely mirrors. It started to look like a place where you could be, comfortable and familiar.”

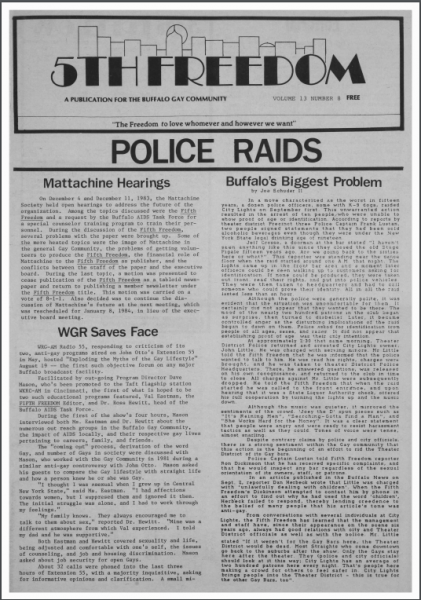

The group created a publication in 1970 called the Fifth Freedom, which can now be found in the Digital Commons at Buffalo State College. Described by the College as “the earliest codified and widely distributed literature of the gay community within the region,” the publication went from being a small pamphlet to being a full-fledged magazine for the LGBT community of Western New York.

“It was quite a wonderful publication,” Madeline said. “People were very particular about the stuff that went in. By particular I mean, the spelling was right, the grammar was right, it was set up visually correctly…Although it went predominantly to membership, it was going to get out, you know? And we wanted it to represent the organization in a good way, and it did.”

It was about this same time that Madeline Davis found herself an accidental spokesperson for Upstate New York’s gay liberation efforts. “It was so exciting. I cannot even tell you how exciting it was,” she said.

“We had heard about the fact that there was going to be a march; people had contacted our organization because they wanted this march to have people from all over the state,” Madeline explained. “It was going to involve a march down the streets of Albany, ending at a plaza that was right in front of the state building…It was a few hundred people, men and women. It was an experience that, I would say, put me into the heart of activism, of gay activism.”

While waiting for the march to begin that blustery March day in 1971, Madeline was approached by the head of the Mattachine political committee. He was collecting a few participants from across the state who would be willing to speak to the group, and needed an “upstate woman” to round out the speaker panel.

“We got to the plaza, and we were standing there with banners and signs and buttons and yelling and chanting,” she said. “It was very exciting. There were so many people. And it came to be my turn eventually, and I spoke.

“I’ll be damned if I know what I said, but I

remember, at the end of my speech, I said,

‘It’s a beautiful day for a revolution,’ and

everybody started screaming and yelling.”

They stayed over in the capitol that night, sleeping on

the floor of the Unitarian Church. “It was so

eye-opening to see all those gay people in one place.

Certainly I had been to the bars here, and there were

lots of people in those bars, but I had never seen

hundreds all in one place,” she said.

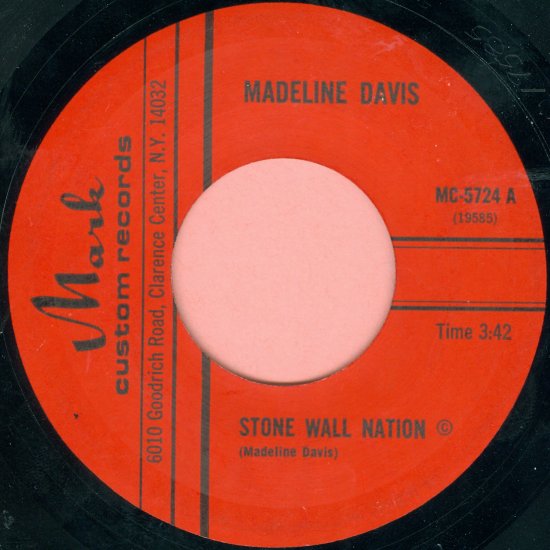

While traveling back to Buffalo the next day, inspiration struck the singer-songwriter. Madeline wrote two pieces that day — one, a poem titled, “From the Steps of the Capitol, 1971;” the other, a song called Stonewall Nation.

And in 1972, Madeline became the first openly gay delegate to address the Democratic National Convention.

Madeline had been involved with music since an early age, and as she became a young woman, was able to turn this creative passion into paying work. While in college she often performed two sets a night, singing “old-fashioned English ballads,” she said. She also wrote and performed original pieces, and sang with an 8-piece rock band of all men.

“When I came home from Albany, my songs changed, and my presence changed because I started coming out on stage. I had not really come out on stage before,” she said.

“When I started getting involved with Mattachine, I started writing gay-specific songs. Those became really popular. I started doing things for groups to earn money for Mattachine. I kind of got to be a fixture in the community, which was a great feeling. People were just so nice and accepting and warm,” she said.

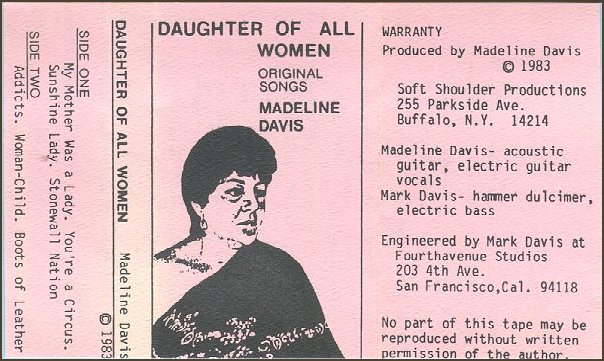

That song Stonewall Nation — written on a scrap of paper while cruising the highway back home to Buffalo — was recorded within the year by the Mattachine Society, and included the accompanying poem on the verso. It is now widely regarded as the first gay liberation record, and was recently included in Pitchfork’s 2018 round-up, “50 Songs that Define the Last 50 Years of LGBTQ+ Pride.”

When asked if she recognized it as an anthem at the time, Madeline quickly answered, “No.”

“But, I get letters now from people who’ve heard it and want to perform it,” she said.

“I remember Craig Rodwell, who owned Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York City — for many years it had been open — and every June he would play Stonewall Nation, over and over,” Madeline laughed. “I’m sure people got sick of it. But actually, from his doing that, people would say, ‘What is that song? Who is that?’ And I got letters and gifts…People would come up and say they were so grateful, and it was the first really gay song they heard, and they didn’t know anybody who sang gay songs,” she said. “That was very nice.”

While working on her master’s degree in Women’s History at the University at Buffalo, Madeline taught a class called “Lesbianism 101,” which was part of the American Studies tract.

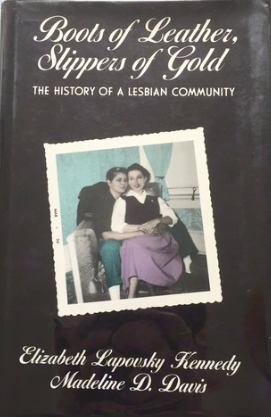

“I decided for a final project, I would send students to some of the older women in the community, and have them interview them,” Madeline said. “So, we talked about the kind of questions to ask, and how to do oral history rather than sociological questioning. I called the women up, and I said, ‘Look, I’m sending you some kids from my class, please be nice. Answer their questions. They’re very nice people.’ So they did, and they brought me back these tape recordings, and they were wonderful. They were just wonderful.”

These interviews were the bedrock for what would become the book, “Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community,” an invaluable reference document still used in universities nationwide.

Madeline brought her findings to fellow Women’s Studies professor, Dr. Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy.

“I said to Liz, ‘Here’s a box of tape recordings from my class. Please listen to a few of them. They’re just great.’ And she did, and she said, ‘They’re marvelous, Madeline. They did such a good job.’ And then she said, ‘Let’s do some of our own. We’ll start a history project.’ So we did,” Madeline said.

“We formed the Buffalo Women’s Oral History Project, and it was just going to be lesbians, you know. We were going to keep the tapes in order, and maybe someday give them to the Lesbian History Archives in New York. So, we were getting more and more, and we started writing papers about the people we interviewed, and how the interview went, and what people said, and the papers turned out to be great. We would do presentations of the papers, usually in June, and some of the people that we interviewed — many of the people that we interviewed — would come to our presentations, and correct us,” Madeline laughed.

By the early 1990s they had enough papers to start creating a book, she said. They pitched the work to a publisher, who enthusiastically took on the project, releasing it in 1993. About four years ago it was republished, in honor of the book’s 20th anniversary.

“It has become really popular and well known in academic circles, and of course now that lesbianism and gayness and transgender have become topics for study, our book has been used in so many universities all over the place,” she said.

Madeline Davis, the natural-born documentarian and professional librarian, had not only been collecting the oral histories of Western New York’s lesbian community during this time, but had also amassed a fairly substantial collection of ephemera and books documenting past and present LGBT culture in the region. Gone were the early days of Mattachine’s community library, where there were more pieces of furniture than books. By the early 2000s she boasted a collection that she recognized needed to be professionally housed, and so she called in an associate from Buffalo State College for an assessment.

“There came the day that we couldn’t push the walls out anymore, and so, I thought it would be really good to have somebody come and look at it,” she said. “A few people from Buff State came, and they were overwhelmed. One person was the head of the history department, one was another archivist, and one was a student, and, particularly the guy from the history department — he was just, I think he felt like he had stepped onto Mars, and didn’t quite know what to do about that,” she laughed. “He didn’t recognize the terrain at all.”

The archivist, Daniel DiLandro, brought the collection to the attention of Edward O. Smith, Professor of History Emeritus and former chair of the History and Social Studies Education department. “He was about 90 years old at the time, and almost blind,” Madeline said. “But he came over, and he took a walk through the archives and said, ‘We have to have this. We absolutely have to have this.’

The College acquired the collection in 2009, naming it after its benefactor — The Madeline Davis Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Archives of Western New York. It has become the region’s largest LGBTQ+ collection, with more than 300 linear feet of items and more than 80 individuals, groups, and organizations represented in the material, dating back to the 1920s.

In 2016, Madeline received a SUNY Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the College.

Madeline Davis has dedicated her adult life to the pursuit of knowledge and justice for the LGBTQ+ community of Western New York. During this time she has seen much change, but the war has not been won. The new generation of activists gives her hope that the work will continue at full clip, however.

“I’m very glad that there are some young people that do have the ability and the interest in working for gay rights, because we’re not finished,” she said. “I encourage young people, if they have any energy and focus on this, to do it.”

The Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project will be presenting two events this week: The Gay Liberation NOW! Reunion Panel featuring former members of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, including Greg Bodekor, Bill Gardner, Rodney Hensel, Don Licht, Marge Maloney, and Madeline Davis. Davis is slated to perform Stonewall Nation for the first time in many years. Thursday, June 27, 6 p.m., at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo, 695 Elmwood Ave.

There will also be a march on Saturday, June 29, which will set off from the Buffalo & Erie County Public Library, 1 Lafayette Square, at 4 p.m. The march will visit the bars, community centers, arrest sites, and protest sites of Buffalo’s gay liberation movement.