Donika Kelly was born in Los Angeles and lived there until she was 13. She then moved to Arkansas where she attended high school and college (BA, Arkansas University). Then it was off to Texas for three years (MFA, University of Texas at Austin), then Nashville for seven (MA, PhD, Vanderbilt University). A dip back into California for a year (faculty, Santa Clara University; University of California, Davis), and now…Olean, New York.

“Last year I applied for a job at St. Bonaventure University, and they were very excited about the possibility of me joining the faculty. I was excited and also kind of unsure – this is a really different place from the other places I’ve lived,” said the 33-year-old poet and professor. It’s a boon for us and the region’s literary community that Donika landed squarely in Western New York last year, however.

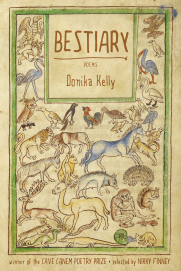

The “Fellowships & Honors” and “Poetry Publications” sections of Donika’s CV are enough to make even the ‘busiest’ of us feel just a wee bit guilty for that day/week/month we spent embroiled in that Law & Order marathon. Not to mention the instructional and professorial career since 2005. Oh, and her first poetry collection, the award-winning Bestiary, was reviewed by the New York Times last month, to acclaim. NBD.

The path to her words wasn’t an apparent one growing up, though. They tried to instigate themselves early on but they were denied, put in storage. It wasn’t time for them, yet.

“When I was in middle school I had written a poem. I don’t remember it at all. But I showed it to my mom and it upset her,” Donika said. “It sounded to her like something that one of her first cousins might have written about being sexually abused by her father. And I was being sexually abused by my father, but my mom didn’t know. That poem upset her, so I tore it up and threw it away.”

Donika is candid. She does not shy away.

It wasn’t until late in the first semester of her senior year of high school that poetry revisited Donika. “And they were terrible,” she laughed.

One of her professors taught Donika how to read her own work. “I’m not an extrovert, but I do like performing; I like the energy. I like making something and sharing it. I had four readings in college – solo readings — faculty came, friends came.” Hastily she adds with a smirk, “There was nothing to do. It was a dry county.”

Still though, it hadn’t fully set in. “It wasn’t until after I graduated from my MFA program [at the University of Texas at Austin, where she was a fellow at the James A. Michener Center for Writers] that I really felt like, ‘Okay, I’m a poet.’ I was in a PhD program and I was still writing lots of poems and I was like, ‘Oh, right, this is the thing that I actually love to do, this is the thing that I enjoy doing. I’m going to do it regardless of whether or not I’m being an academic or being a scholar.’”

“Poetry gives me some space to be in something for a few minutes; we can just be in this for two minutes and then we’re out. How it moves might be surprising, but that surprise is in a moment, and then you can dip out.”

Donika knew the New York Times review was coming. She read it for the first time along with everyone else, however.

“So – I like my book. I want to preface everything that I’m about to say with that. I really like my book. I wouldn’t have sent it out if I did not think it’s a strong piece of art,” she states. “But as we know, making a good piece of art, making a strong piece of art, doing good work doesn’t always result in recognition.”

I just didn’t expect that I would be on the radar in any way.

Bestiary was the recipient of the 2015 Cave Canem Poetry Prize and was longlisted for the 2016 National Book Award for Poetry, by the way.

“I understand some things about America – who gets to count as a person, trends in art, who is recognized – I just didn’t expect that I would be on the radar in any way. Now I have to reconfigure in my head, ‘Oh, this is not how I thought it would be.’ That’s good, people are reading the work.”

Living in the 93 percent white, 15,000-someodd-person town of Olean is different from Donika’s previous places of being. “It’s a funny little town,” she said. “I had some anxiety after the election, but generally people are kind. We’ve had this freakishly warm weather, and so my neighbors are talking to me a little bit, which is nice. They’ve been pretty quiet the time I’ve been there; it’s not a hostile space, but it’s not a warm space. It’s a little bit difficult being a black woman in a town that is over 90 percent white – it’s a challenge.”

The concept and actuality of safe places of being are concerns that not everyone has to share, but that are absolutely at the foreground of the current political climate. “I’m very vulnerable. If I think, ‘If I could be anywhere, where would I want to be?’ I have to think politically – where is okay for me to live? Where will I be safe? Where will there be legal protections for a person in the body that I occupy? I think there a lot of white people who just don’t ever have to think about that; they can live anywhere. I wonder what that’s like?” Donika is succinct and accurate.

“There are a lot of white supremacist groups that are emboldened right now; it feels really scary,” she said. “It feels really scary to be in a part of the country where it’s difficult to understand what the racial dynamics are.

“In the South it’s all so clear. Here I know that there’s racism – on my way up [to Buffalo, on Route 16] there are two Confederate flags, huge Confederate flags flying outside of people’s homes — I’m affronted every time. ‘This is not supposed to happen up here.’ The narrative that I’ve been told, even though I know that it is false, is that this doesn’t happen here.”

The university, bastion that it often is, has been incredibly supportive during Donika’s tenure there. “The school is engaged in new initiatives that feel welcoming and open to bringing in different kinds of voices,” she said.

She continues: “I’m out on campus. I feel that’s important for students in a number of ways, so that they know that, if it’s hard for them right now, there are people that are alive and happy, you know? That happiness is a possibility, joy is a possibility, work is a possibility. So it feels important for me to be out,” she explains.

Indeed, she brings this honor to truth to her classrooms. “I really enjoy talking to students about gender and about what they’re bringing to the table, because part of what I’m interested in is showing them that they learned that somewhere,” she said, unpacking one of her fields of expertise, gender studies. “That it’s not natural, that it’s not inherent; they learned to see things in a certain way and to understand those things as normal. Figuring out ways to talk to young people and different kinds of young people from different backgrounds about those same issues? It’s a challenge that’s very welcomed.”

The use of language to convey precise ideas is a wicket that is ever-evolving, and Donika excitedly explores its murky edges.

“Teaching gender studies and literature classes, trans students, queer-identified students, students of color, students from working class or working poor backgrounds, they put pressure on language in ways that are really surprising…As a poet, I’m just like, ‘Yes. Let’s put pressure on this language, let’s try to be as precise as possible, understanding that language is going to fail us at every point,’” she said.

“I’m really interested in how to describe things. How do I describe something as precisely as possible, understanding this failure?”

The trajectory forward is one of work, good work. Writing, teaching. Dialogue. More hugs.

“All I try to do is good work; it’s the only thing I know how to do. By that I mean, try to figure out how to make art that I want to share,” Donika said. “I have my standards for what that means. Sometimes that standard is just a feeling, ‘Oh, this is good, I want to share this with people.’

“I’ve gone through times that are pretty fallow. I think, ‘I should be writing.’ But I’m not, and it’s okay. I have patience and tend to other things that need tending to. I don’t know. It feels…good. I feel good about the art I’m making, and I feel good about sharing the art that I’ve made with the world.”