Did we like tattoos? Of course we liked tattoos. Did we own records and grey jeans and drink pour over coffee and know the difference between third and fourth wave feminism? Of course we did. Did this make us elite and lucky? Did this make us uniquely self-indulgent and American? Yes. Did we do this as an act of love? A romantic invasion? A means of connecting ourselves to Tony? Maybe. Were we moral? Could we feel the change in ourselves? Did we think of ourselves as violent and cruel? Did we know we’d feel stained afterwards? Dirty? Always bad? No. We didn’t. How could we know that? How could we feel emotions for events that we hadn’t experienced yet? No one had taught us to have this kind of empathy for our future selves. No one had told us that this might be wise to consider. No one told us anything except to smile more, look less angry, to talk with less spit in our mouths.

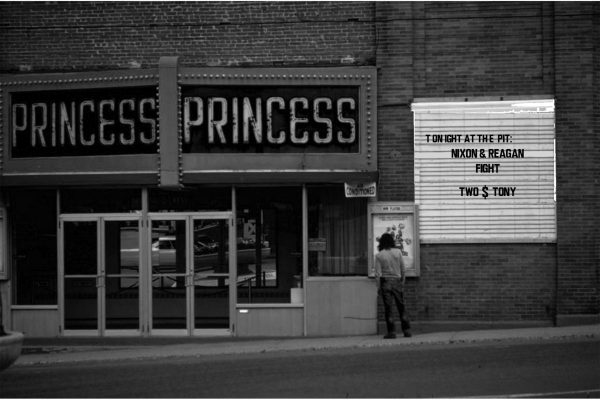

We were street artists, muralists. We had one or two commissions a year. You don’t understand how hard it is for small, young, angry women like us to get money. To get this much money. We had worked as bartenders and baristas, waitresses and retail clerks. We were sick of being overqualified. We were sick of men getting commissions and money and blow jobs. We thought of The Pit as a kind of performance art. We thought it’d make all of us better. We changed our names from Katie and Deb to our stage names, Reagan and Nixon, as some kind of trickle-down-white-man-take-down satire. We ended each fight with two peace fingers in the air.

The fights were arranged by a guy named Hans Maxfield. Were we in love with Hans? Not entirely. Maybe Deb a little more than me. Were we in love with Tony? Probably. It would explain a lot. But, he was hard to love, maybe a little asexual. Tony was thin and quiet like a cricket. With dark beautiful hair and good taste and maybe even ambitions, but he was so messed up inside. His dad was a shoe cobbler. He repaired Tony’s shoes every six months. Tony was the kind of guy who didn’t eat much and had one only pair of shoes, but they were made of such beautiful leather. His shoes almost made you want to cry for how messed up class is in this country.

Hans Maxfield lived in the nicest street of our city: Rumsfeld Terrace. He lived in a pale blue house. He had a garden. He had a black lab named Groucho. Hans had a thick German accent. He was punctual. He was fifty years old and kissed with the desperation of a soldier. We had met him at a wedding when, drunk and sweaty, we walked to his house and he played the piano for us. We had too much wine and the salty burn of each other’s breath in our lungs. He alluded to family members who buried their uniforms. He alluded to a brother who was gay and missing. He alluded to far away bank accounts. He bought nice, lovely pinots. The kind of pinots bought by someone who had enough money to understand the complexity of pinot. We thought he’d understand us because of his empathy for fermented products. He had intricately woven carpets in each room of his house: rouge and black and cream. He had a big thick neck. He spoke like a jam jar opening. He always did this thing at the end of his sentence, where he lifted up his voice in a uniquely German way, “You’re on at 11pm, yah? You’re okay with that, yah?” The “yah” was a small, yellow yawn at the end of the sentence that floated off into the back of his throat and ours.

Hans Maxfield was smart, bad money. I could see this is in his shaved neck. It was so perfectly shaved except for one little patch, one continual patch near the right side of his throat, that he missed every single time. The first time I kissed Hans, I wondered if Tony would kill himself. Tony was on the couch, pretending to read a book about race horses, but I knew he saw this kiss. I wondered how much he loved me. Tony was always threatening to kill himself. We never knew when he was joking. We used this later to justify what we did. We thought he didn’t see his life as very worthy. Even though, to me, I thought he was someone pure and good and maybe a little like an endangered animal. Someone you want to save but also know why capitalism is based on Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Deb was pissed off that I kissed Hans. She grabbed Tony by the hand and they smoked cigarettes alone together in the parked Ambassador in Hans’ garage. There are little marks on the leather where the cigarettes fell out of their mouths, marking the moment when they felt the soft velvet of one another’s bellies. Back then, we had easier problems. I wish I had that problem now.

When Deb and I were in the first fight, we thought of it as a play. We weren’t ourselves. We were fake dead presidents. We thought smashing someone in the face wasn’t really going to destroy them. We thought of ourselves as artists. I had painted a wall in our city: a big blue and yellow mural of a 1960s beach scene that said “The Rich Are Invisible!” Tony said it was good and true because he hated the rich. I wanted him to see as me as different, as better. I wanted him to find my sloppy nose, my leathery skin alluring. I wanted him to love me more than all the others. My murals were banal, hackneyed, simplistic, but back then I thought, like many things about myself, they were revolutionary.

When they paid us the money for that first fight, we thought it was all going to be fine. We didn’t even spend it. We saved it in glass jars under our beds. We put five hundred dollars in one labeled with Tony’s name. It was intended to be a gift.

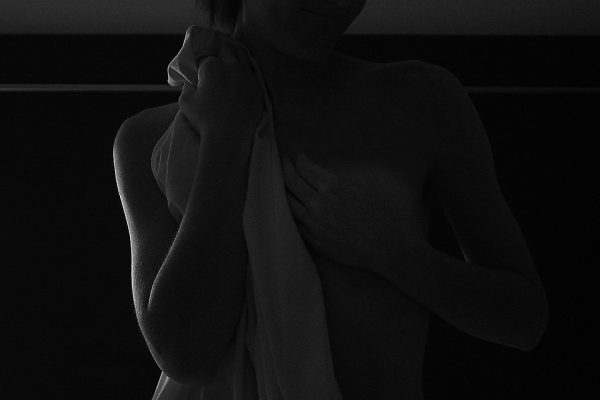

For us, it was a weird kind of feminism. Something like roller derby. Only we’d fight against small men. I was 5’8 and Tony was 5’2. When I felt his jaw on my knuckles, it felt a lot like romance. But, later, when our bruises smeared dark over the inky roses of our skin, I saw it only as stupid. I don’t think Tony ever felt anything for me. He was hung up on someone named Shelly Alain. I didn’t know much about Shelly and I never really wanted to.

We were twenty-three years old and we thought fighting was better than cocaine or getting drunk every goddamn night, which we were still doing after fighting in the Pit, but were doing in a different way. We were so hungry back then, in so many ways. We ate good, big pizzas from “Thick Nobodys,” the shop near Hans’ house. They were big yellow circles of grease and bombs of pepperoni that made our stomachs tighten and turn. We were too scared to shit in Hans’ house, so we held it until we got home to our little apartment with the lamps covered in wheat paste maps of places we’d been when we were children.

We didn’t know the strength of our arms because we had never used them. We didn’t know we would enjoy the feeling. We couldn’t stop it once it started. We punched Tony with closed fists and then we got so riled, by the crowd and the music, and the energy of the ring with all these sweaty people throwing cans of PBR at our feet and telling us we were beautiful, confirming that, yes, this was the answer.

We opened our hands; we shot our palms up under his chin and pushed his head back. It felt wonderful and real and made us whole, in the way that sleeping with someone makes you whole, if only for the crescendo. In the fight when Tony’s neck snapped, his mouth guard fell on my bare foot. When I saw him lying on the plywood floor, he curled his head into his hands. He looked like a skinny calf fallen from the womb of an animal mother. We didn’t feel bad. We felt good. We felt like we had won something we deserved. Something that had been owed to us for a long time. Something we had lost in the election. Something we had lost hundreds of years ago and we were just getting it back now.

As we fought more, we saw that The Pit was funded by dirty money. Mafioso guys who orchestrated fake wars. All the real wars had been solved in the 1980s and now all they cared about was calorie consumption or if their streaming TVs worked. They had to create these boxing matches for something to care about. Something bad and awful that they could believe in. A universe where the logic was simple and made sense to them, despite it being corrupt. Maybe they saw themselves as progressive, too. Mafia feminists. I don’t know what they fuck they thought. Maybe to them, we were still just the weak, beautiful other. Maybe we were just a strip club.

When we learned that Tony was really hurt, we thought it was temporary, like a broken arm. We thought he could be stitched back together, with a small scar and a good story.

The announcer, “Down for the Count Kenny,” raised our hands up and mine caught on his bowler cap. I realized then that the hat was fake. It wasn’t nice, soft felt like I had originally thought. It was hard, cheap plastic. It was leftover from his halloween costume as a kid.

I left the ring with the memory of a little blood on my Keds, and how still Tony was. Weirdly quiet and still. I saw his neck curl farther into his spine, like he wanted to go back to being an infant. But, Tony didn’t die. He got better. Finally.

We had stopped boxing by then, but, we didn’t talk to Tony anymore. Our friends said they saw him at the cafe. Said he spoke with a weird slur, said one of his eyes had gone cloudy. They said he was still kind of good looking. He still wore those heartbreaking leather shoes but the laces were tied all wrong. Hans stopped calling after we stopped fighting. Deb and I hung out only with each other. We lived in a universe of only the two of us: our new rules, our new codes, our new unspoken morality. We spent our time at beaches late at night. Went to the ones up in Canada. The ones that smelled like suntan lotion mixed with gasoline, like so many places now.