“I came out as gay to my family when I was 16, and got nothing but tremendous support,” Marge said. “As I got older, I realized that not everybody was that fortunate. That began my activism, and my idea of haves and have-nots; people that were more privileged in some ways.”

She has been an active member of the Workers World Party (WWP) since 1969, when she, as a college student, joined the party’s youth caucus.

“I got involved in the anti-war movement, which so many of us did. It was ‘69 when I joined the anti-war movement, and it just sort of flowed from my ideas about struggle and oppression,” she said. “It was intersectionality before it had a word.”

In addition to labor rights, the WWP worked to support food justice, prisoners’ rights, Middle East liberation, and LGBT and women’s issues.

The Gay Liberation Movement

The Stonewall Riots happened during the same time that Marge found herself deeply ensconced in anti-war efforts.

“I was so busy doing anti-war work and being a thorn in the side of authority that I didn’t pay much mind, truthfully,” she said. “I was working, going to school, and running the streets with the cops chasing me.

“The gay movement in Buffalo was nascent for a long time. I mean, there were people back in the ‘50s and ‘60s obviously, but I came to the LGBT movement late. I was beginning to have an inkling that I was destined to struggle, and so I joined the Workers World Party, because they were at the time the only socialist party to have both a women’s caucus, and a lesbian and gay caucus, both fully functional,” she said.

“One thing led to another, and they just perfectly dovetailed. I could be active in the gay community, and I could be active in the workers’ struggles, and the tangential struggles that came from it. It just sort of worked beautifully.”

The Mattachine Society

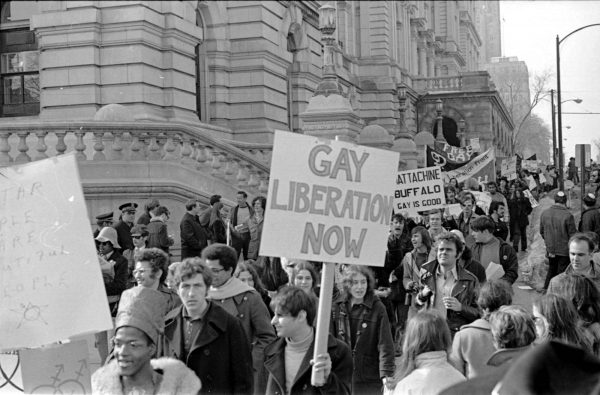

Marge attended the March on Albany in 1971, joining the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier shortly after. This organization was a much more mainstream effort than her other, more radical efforts with the WWP. She joined Mattachine’s Speakers’ Bureau, who organized conversations with fellow community organizations, such as PTAs and the University at Buffalo’s medical school.

“We answered questions from all of the med students about being gay and transgender, and tried to raise their consciousness a little bit. ‘We have the same hardware that you have, we deserve the same respect,'” she said.

Marge helped to build Mattachine’s gay and lesbian community center at Main and Utica. “We provided counseling, a drop-in center, and meeting space for people and community organizations,” she said.

At this time, Marge was working in the Women’s Studies department at the University at Buffalo. “We had a socialist-feminist bent,” she said. “I taught the intro course, ‘Women in Contemporary Society.’ I also taught a lesbianism course called ‘Woman to Woman.’ It was pretty fun. We had Saturday night dances for the women, and Friday night for the guys, just like record hops in the ‘50s.”

Memories of Villa Capri

“It was a pretty tough bar. They were used to fighting for their rights, and used to not taking any shit, and getting beat up for who they were. It was a fun bar,” she recalls, describing one of Buffalo’s storied lesbian bars of the past.

“There was one incident — it was at Main and Allen, where the transit station is now — and some guys tried to come in. It was the St. Patrick’s Day parade — white, drunken, suburban guys came in, drunk off their asses, and tried to get in the back room, which was strictly reserved for… things. Without even thinking, all these women, in unison, moved together. Every time the guys tried to go past, the entire bar would just move and block them. It was a little cat-and-mouse game, for about a half hour. Finally they decided that this was no fun. I’m thinking, ‘Oh, you made the right decision… or else we’ll bust your ass.’

“We always depended on each other; there was nobody but yourselves. You walked tough because you had to be tough, and whether or not you were was irrelevant. You had to put on this facade. I mean, don’t get me wrong — these folks could take on an army. But again, it comes from the struggle. You struggle every day to be accepted and to live your life, and every day you’re oppressed by people. You just had to put up with shit all the time.”

Buffalo United for Action

“We formed a self-defense group — Buffalo United for Action, which brought the gay community and the pro-choice community together,” she said. “We were part of the same struggle. The same people that were oppressing us are telling women they can’t have control of their bodies. And, guess what? Lesbians are women. I know, it’s a shock, but get over it,” Marge laughed.

“So what we did was form clinic defense groups, and we would go out and defend a clinic. Because of this, not one clinic was shut down,” she said.

“We had young people — they were so cute, I love young people — they were climbing trees to keep an eye on the antis. One doctor was on Linwood, and Womenservices was over on Main and Northampton — they were sort of close to each other, and the young people would climb the trees and keep tabs on if the bad guys were coming.

“It was like a little mini city — we had our own defense, we had our own security detail, we had our own phones, we kept tabs on each other and them. There were 500, 600 people involved. We were there every day.”

The Rainbow Peacekeepers

The Rainbow Peacekeepers started with about 100 active members who acted as watchdogs for the city’s gay bars. Marge was one of the group’s coordinators.

“We would have groups of people go to all the bars on the weekend [Operation Save America] were going to be here, and if there was any trouble or if it looked like there was going to be trouble, we had them do what we told them in our training classes: ‘Don’t engage. Take their plate numbers, their car types, and their description. Give it to us, and we’ll get it to the cops.’

“We were very disciplined. You had to report to us, then you would go out from our headquarters and check all the bars and see what was going on, if anybody needed anything,” she said. “We were out there defending the clinics in the morning and the bars at night. And this was when many of us were still working. And again, because we were organized in our own little self-defense groupings, not one bar was shut down — they didn’t even try it.”

The New Generation

She continued: “Young people are making all kinds of connections, and it’s pretty much on their own. I mean, there’s nobody giving them a playbook — they’re just doing it by themselves. I think that’s tremendously exciting.”

When asked what the younger generation of activists is doing right in their struggle for justice, Marge was quick to explain: “They’re organizing. They’re educating themselves in the struggle. They’re acquiring skills, they’re able to talk to people.

“They can have vast networks and they can exchange ideas and get together… They’re respecting the elders… There seems to be a reach out more to older people to get their experiences,” she said.

“It’s a different kind of activism, and in fact, history is not static. History is always moving forward, and new formulations happen, and I think this is just a different formulation of the same activism.

“I think they’re a lot more versed in theory. They understand society I think a little bit better; they have a broader perspective. We saw society as something to overthrow. We saw society as a thing that oppressed us, and wouldn’t let us live. And these kids see that also, but they see it from a broad perspective.

“I think it’s an exciting time to be young, it’s an exciting time to be an activist, but it will bear no similarities to what we did when we were young,” she said.

However, she cautions the new generation to have patience: “I think sometimes young people want something done yesterday, and the process of achieving yesterday, they don’t realize there were a whole bunch of before-yesterdays. They’re strong. They’re bold, certainly. They seem to have taken the challenge to change society, and they’re doing it in an interdisciplined way.

“It takes a certain amount of dedication to be an activist your whole life. Things change, situations change, your life changes, you know… It’s a generational thing, every generation learns something… I hope they continue their activism as long as they can.

“I would hope that they’re aware that what they’re doing is a quest, and it’s not going to happen overnight and they can’t get discouraged. I mean, I’ve been knocking around for 50 years. It’s been a long time. And the fact that the struggle’s still the same thing… I’m hoping that the young people can focus on something besides the time. It’s not going to be a day, it’s not going to be a week, it’s going to be probably their whole life.

“I keep thinking, ‘I cannot believe I’ve been dealing with the same issues for 50 years.’ I keep thinking, ‘Wait, didn’t we do this?’”

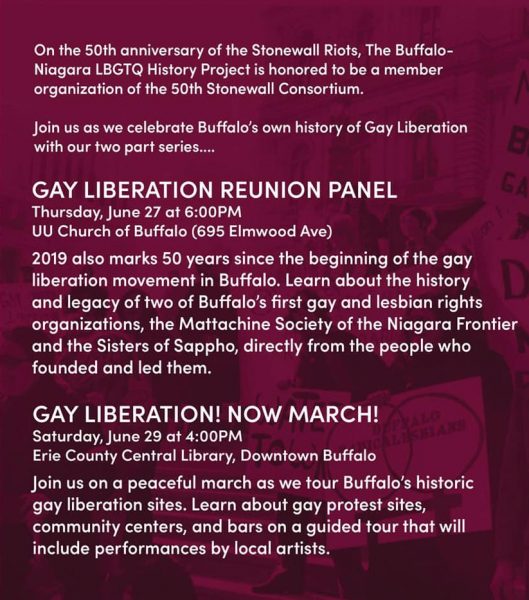

The Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project will be presenting two events this week: The Gay Liberation NOW! Reunion Panel featuring former members of the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier, including Greg Bodekor, Bill Gardner, Rodney Hensel, Don Licht, Marge Maloney, and Madeline Davis. Davis is slated to perform Stonewall Nation for the first time in many years. Thursday, June 27, 6 p.m., at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo, 695 Elmwood Ave.

There will also be a march on Saturday, June 29, which will set off from the Buffalo & Erie County Public Library, 1 Lafayette Square, at 4 p.m. The march will visit the bars, community centers, arrest sites, and protest sites of Buffalo’s gay liberation movement.